rhyming game during a self-described "boring car trip" with her young children inspired Nancy Shaw to write Sheep in a Jeep. Since its publication in 1986, her hapless critters have returned for more escapades in Sheep on a Ship and five other related titles.

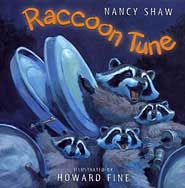

Her rascals of a different species bring just as much fun in Raccoon Tune, which was selected as the 2008 featured book of Michigan Reads!, a statewide program to promote early childhood literacy. While these books may be short, writing them is anything but child’s play.

Photo from Nancy’s website. Cover reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

WOW: It's a pleasure, Nancy, to have the chance to talk about writing with you. Your books have been big favorites with my nieces and nephews. With your background in English literature study at Harvard and the University of Michigan, it's no surprise that you became an author. Did you start out wanting to write for children or did these goofy sheep and their runaway jeep lead you in that direction?

Nancy: I had been interested in kids’ books for a long time. We had a kiddy-lit unit in high school, and I shelved picture books as a part-time job in college, so I stayed in touch with them. I first tried writing one when I was in college, but I never had a story published until I had been reading to my kids for quite a while. Reading lots of books, and noticing what kids like, is good training. My kids liked silly stories.

A couple of my high-school English teachers made me aware of word origins and sentence rhythms. On the college level, reading centuries of classics makes you think about language nuances. When you boil down a story to a minimum of words, you want to pick them well.

WOW: Yes, these books are, at their heart, poetry, and the language has to be as tight as any poem, whether it's written for adults or kids. And kids today have been primed so much by their exposure to different media. The mini bio on your website mentions that your family didn't have a TV in the house until you were in the third grade. How did that affect your relationship with language?

Nancy: I became a big reader, and that expands your vocabulary as well as your sense of what’s out there in the world.

WOW: And your expanded sense of the possible plays out in your books with their delightfully unpredictable rhythms. What tricks do you use to keep rhyme from degenerating into sing-song?

Nancy: Focusing separately on the sound, and trying all kinds of things to get around problem areas—like using synonyms, or rearranging word order. It can be like doing a puzzle. I like working with rhythm and rhyme for kids. I think the patterning helps little ones grasp the language. It’s always a battle to avoid sing-song. Short lines speed up the action and longer ones are more lulling, but the lines don’t always co-operate. If you work in traditional forms, sometimes you’ll be hemmed in. There are times when I just can’t find a rhyme to say what I want to say, or I can’t seem to break out of a too-regular rhythm.

Though you might sometimes sacrifice exact meaning for the sake of rhyme or meter, putting rhymes together can also lead you to thoughts you might not have had otherwise. My books tend to start with the sounds of the words, often with a phrase or couplet that gets into my head, and I see where they lead me. I always have to shift back and forth between where I want the story to go, and what the rhymes will let me do.

“I always have to shift back and forth between where I want the story to go, and what the rhymes will let me do.”

WOW: And with picture books like yours, you're not just at the mercy of the rhymes. You also have to consider the illustrations, which are such an integral part of the story for beginning readers. How does that need to be visual affect your pacing?

Nancy: The illustrator decides which lines go on which page, and most editors wouldn’t want a writer to try to manage how that’s done. But before sending in the text, I try to demonstrate to myself that there’s at least one workable way to lay out the story, and that I can visualize something for each spread. I grew up in a family where artwork was emphasized, and I liked to draw, but the pictures I did for test dummies had nowhere near the panache of Margot Apple’s and Howard Fine’s work.

I was thrilled by how much life the pictures added to the text. They really enriched the story rather than just telling it. When I made simple drawings for my neighborhood testing copy, I drew two sheep. A tow truck pulled them out of the mud. Margot Apple brought a bunch of sheep into the story, with vivid personalities, and tattooed pigs pushed the vehicle.

WOW: (Laughs) Having tattooed pigs suddenly appear in your story would be a surprise alright. Was there anything else unexpected when the book itself came out?

Nancy: I was pleasantly surprised that the story got as much attention as it did, and since those early days, by how steadily the book has sold. It’s in multiple editions, and it’s been part of a reading program. I paid some attention to writing a story that would be easy to sound out, and I even thought for a while that it might be an easy reader. But telling a story was always the main thing.

I didn’t imagine back then that the sheep would go on to have so many adventures. They’ve been sailing, shopping, dining out, hiking, trick-or-treating, and orbiting. I was heartily sick of the “eep” syllable when I finished the first book, but then the “ip” syllable crept in and I started tinkering with it, and the sheep went off to sea. Sheep on a Ship was even in an animated version on the PBS series Between the Lions. The show works on reading skills.

WOW: After the ship, your sheep went on to other adventures, and then took a break for about a decade. What brought you back to the fold last year for Sheep Blast Off!?

Nancy: Sheep Blast Off! had been sketched out earlier, but hadn’t quite worked. It was dormant for quite a while. Eventually I scrubbed the plot—which had been about failure to launch—and got a new plot in place.

WOW: But even as the plots have changed, the one constant has been Margot Apple, the illustrator for all the Sheep books. How much input have you had with her artwork?

Nancy: It’s not unusual for a writer and illustrator to have no contact with each other. I had none with Howard Fine until several years after the publication of Raccoon Tune, when the book was named for Michigan Reads! The publisher will choose the illustrator and will want each person to work in his or her own way, without either telling the other what to do. If a writer feels a need to express an opinion, it often goes through the editor. I met Margot after the first three books were done, so on some of the books, there was direct communication.

WOW: Since you hadn't collaborated with Margot on the drawings, what was your reaction when you first saw your words merged with her artwork?

Nancy: These sheep are wonderful!

WOW: Oh, I agree. After all your good times with the sheep, what was the new inspiration for Raccoon Tune?

Nancy: It may go back as far as graduate school, when I babysat a boy who loved raccoons, and I first thought about raccoons singing and dancing. The direct inspiration was the mess raccoons made with our garbage cans. I had to admire their work ethic, though, and I imagined them celebrating. They look for supper in garbage cans, and find it in a way they don’t expect.

“Often the best parts come quickly, but I have never been able to sustain a whole story in the first burst.”

Cover reproduced by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company. All rights reserved.

WOW: The raccoon's "work ethic," as you say, led to a more complex story line than your previous books. How was writing it different?

Nancy: The stanza pattern is more demanding. I got stuck and put it away for years.

WOW: Occasionally getting stuck—that's something most writers have in common. What do you find to be the hardest thing about writing for young children?

Nancy: Often it’s a challenge to find a satisfying plot arc, with the right level of problem to resolve.

WOW: And the greatest joy?

Nancy: I love it when an idea hits me and I think I can do something with it. Also, seeing the finished book and seeing how it’s become something more—the special touches with the sheep, or the inventiveness and pop-off-the-page quality of the raccoons. And of course, when a child enjoys the book, that’s the whole point of it.

WOW: And if it's simple enough for a child to enjoy, it must be simple to do, right? (Laughs) Readers may see a book with only a few hundred words and think it was rattled off in an afternoon. How many revisions do you typically complete between first draft and final submission?

Nancy: Often the best parts come quickly, but I have never been able to sustain a whole story in the first burst. I rework numerous times, so I don’t count the drafts. I often let a story rest—sometimes for a ridiculously long time. The shortest time from inspiration to final text has been 14 months.

The first sheep story got started because I was bored on a car trip. Since I’d just been reading some animal rhymes to my daughter and son, I tried making up more. A bunch of rhymes clustered around sheep, and I tried to make something out of them. The main idea was probably set in twenty minutes. After two and a half years, and seven rejections, I came up with the final text.

WOW: During those revisions over the years, what were you watching for?

Nancy: Children’s writers may distill stories down to a simple structure, and indeed it doesn’t look like there’s much there, but often a lot has been tried out and reworked. I watch for parts that don’t advance the story. The editor who brought the sheep books into the world sometimes had to make me notice this. She was very good at pointing out tactfully that a story needed more internal logic—that things can’t happen just because they rhyme. Expert editors have been crucial to my books.

I also look for places where my meaning doesn’t come across. It might be obvious to me, but not to a five-year-old. Or to you.

“I also note the fidget quotient while I’m reading aloud!”

(Photo: Nancy’s Grandmother reading to her when she was very young. From Nancy’s website.)

WOW: How do you ensure that the meaning does come across? Do you test-read your manuscripts with children while you're developing them?

Nancy: I was more methodical about testing when I started the sheep books. I would ask parents I knew to read the story and relay their kids’ reactions. I thought they could be more objective than I would.

WOW: Do you also get feedback from kids during your elementary school programs?

Nancy: If I read a work in progress to a school class, I ask if the piece is clear, interesting enough, ready to send out, and sometimes about certain details. I get useful feedback. And I want kids to know that rethinking is part of the process. I also note the fidget quotient while I’m reading aloud!

WOW: Ah, the fidget quotient—a fool-proof assessment tool. Which children's authors have kept you glued to your seat?

Nancy: I have so many favorites! Just for a few, I love Beatrix Potter, James Stevenson, David Wiesner, Susan Meddaugh, and Paul O. Zelinsky. They’re all author-illustrators. I love their artwork as well as their storytelling. A favorite writer is Jerdine Nolen—she’s so imaginative and her language is so flavorful. One thing I admire is writers who are witty and able to put that on the reader’s level.

WOW: You're right, hooking young readers on their own level is essential if you want them to grow into life-long readers. That's what makes the work of Michigan Reads! so valuable. What activities have you been involved in since Raccoon Tune was selected as its featured book?

Nancy: Michigan Reads! kicked off with the Target Book Festival in August. During September, I went to a number of libraries and schools around Michigan to read stories, and took a garbage can and recycling bins. Librarians were wonderful at singing raccoon songs and helping me act out a “litter-ary” skit. The programming guide with songs and lots of activities, is available online. I love having a statewide book program, because it calls attention to the importance of early language. The Library of Michigan chooses a picture book to share with libraries, early elementary grades, and preschool programs.

And before that, something else cool happened to the raccoons. The Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra commissioned music to go with the book. Joshua Penman wrote an eclectic score with a narrator raccoon. He liked the trash-can cymbals on the book cover. The drummers wore raccoon masks and played can lids!

WOW: That's a great way to introduce kids to both music and books and bring the words to life with a bang. On a quieter note, what advice would you give to women who want to write picture books?

Nancy: I’d say to read a lot of picture books, so you have a strong sense of story and language for this age and a sense of which publishers might be a good fit with your work. It helps to develop an awareness of structure. If you can find a good critique group, weigh their input, and experiment with your stories. Taking in criticism takes practice. The Society of Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators provides resources, including ways to network.

WOW: Great advice! Thanks, Nancy, for taking the time to chat with us today about picture books.

***

Barbara J. Petoskey is a freelance writer whose short fiction, essays, articles, poetry, and book reviews have appeared in a previous issue of WOW!, as well as Writer's Digest, Detroit Free Press Magazine, Bostonia, Cat Fancy, and The Bloomsbury Review. Her work has been collected in books such as The Best Contemporary Women's Humor, The Writer's Handbook 1996, The Bride of Funnyside, and This Sporting Life. As a contributing editor for ByLine magazine, she published more than 100,000 words in her monthly columns.