ost authors would like to see their work adapted for the big (or small) screen, but the path from here to there is, at best, unfamiliar—and can seem incomprehensible.

Some best-sellers are made into movies; others ignored. Even obscure books, short stories, and magazine articles are blessed by Hollywood’s magic while thousands of screenplays are turned away. Harry Potter sells to Hollywood a mere year after publication while The Lord of the Rings takes nearly five decades to hit the screen. What sense does that make? Is there no rhyme or reason here?

Well, yes, actually. But it’s hard to make out when—like most writers—you’re on the outside looking in. This article will take you through the looking glass and make some sense of the enigma that is the Hollywood adaptation process. More importantly, it will explain why some books are made into movies while others are not; and what you can do to make your book (or story) more attractive to filmmakers. To do that, we’ve pooled our own knowledge and consulted several friends in the industry.

“When it comes to the screenplay itself, I look for a unique voice and singular vision that set the writer apart, and a powerful story that I can’t put down once I’ve started reading.”

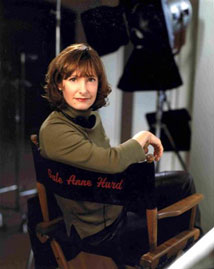

(Photo: Gale Anne Hurd, Producer)

Industry Players Speak

Gale Anne Hurd is the first woman to join the ranks of Hollywood’s previously all-male Big Budget Action Club. A graduate of Stanford University, she co-wrote and also produced The Terminator and has since gone on to found her own company (Valhalla Motion Pictures) and produce over thirty films and five television features. Much of her work has been wildly successful, and her films have been nominated for numerous awards, including fourteen Oscars. She sits on the board of the PGA (Producers Guild of America) and is a winner of the Women In Film Crystal Award.

Gale’s work runs the gamut from young adult like Clockstoppers and family dramas such as Safe Passage (adapted from the novel) and The Wronged Man (based on a magazine article) through adventures like The Ghost and the Darkness (based on a true story), comedies like Dick and Dead Man On Campus, and horror such as Bad Dreams and The Relic (based on a novel). She has also produced big-budget action fare like Armageddon, Aliens, and The Abyss as well as the Terminator, Hulk, and Punisher franchises (the last two adapted from graphic novels). Most of her upcoming projects are adaptations.

“I respond to character-driven material, regardless of its origin,” Gale says when asked what draws her to adaptations. “I fall in love with the characters and generally respond to stories featuring ordinary people who succeed in overcoming extraordinary challenges.”

Many such stories do not start out as screenplays. “From the true story of Calvin Willis being released from prison after serving twenty-two years for a crime he didn’t commit—which was based on a GQ magazine article—to The Incredible Hulk showcasing Bruce Banner’s attempt to control his rage in the Marvel Comic, underlying material has so much to offer writers and producers. When it comes to the screenplay itself, I look for a unique voice and singular vision that set the writer apart, and a powerful story that I can’t put down once I’ve started reading.”

Director Lesli Linka Glatter began her career as a dancer and choreographer. Her directorial and producing debut—Tales of Meeting and Parting—was based on a series of true stories and earned an Academy Award nomination for best live action short film. She has since directed several features and TV movies and dozens of episodes for series including Twin Peaks, NYPD Blue, Gilmore Girls, The O.C., The West Wing, Grey’s Anatomy, ER, Weeds, Mad Men, The Mentalist, and House, M.D.

Lesli sits on the board of the DGA (Directors Guild of America), won this year’s DGA Award for Best Director of Dramatic Series (Night), and has five feature films in development—three of which are adaptations. She also directed the pilot for a new series called Pretty Little Liars (based on the series of young adult novels by Sara Shepard), which was recently picked up by Warner Brothers for ABC Family.

“I’m a huge reader,” says Lesli. “So, adapting things from other sources is something I am somehow always pulled to. For me, the material has to have a strong theme, some sort of purpose—and whether that’s to make you laugh or cry, or to be a great ride, there’s got to be some sense of connection to what it means to be human.

“I’m also attracted to true stories. I’m always interested in that one experience, that one thing that happens that changes your life forever, and you’ll never be the same—because everybody has those even if they don’t realize it at the time.”

Screenwriter Teena Booth is also drawn to adaptations. She began her fiction career as a novelist and then switched to screenplays after winning a Chesterfield Screenwriting Fellowship. Teena has written eight produced TV movie scripts—most with female leads. Five of those were based on books or true stories. Three of them air this year.

“I love to get hold of a great idea I would never have come up with on my own,” she says. “It always seems a privilege to be able to borrow someone else’s imagination. Facing a blank page is, in many ways, an exercise in torture; but working on an adaptation takes the torturous component out of the creative process, leaving me the much more enjoyable work. I look for a premise that seems to offer a range of emotional conflicts and possibilities to explore, and hopefully a character or two I can relate to and/or have fun with.”

Still, regardless of personal preferences, the writer must also craft a story that appeals to the Hollywood studio system. Because unless you plan to finance the film yourself, you will at some point need to keep a studio happy even if all they do is distribute your finished film. And the studios’ world is one of harsh financial realities.

“I trust my instincts on story,” says Julie Richardson, who produced Collateral for the big screen and Nice Girls Don’t Get the Corner Office for television. “But I've also learned that instinct is only one woman's opinion. So, I develop stories I believe I can sell. There are any number of ways to develop a project, but not all of those are commercial. Studios don't want something they cannot sell. Even outside the studio system, those who invest in the film want and deserve our best efforts to ensure a profitable return.”

Like publishers, film studios and the production companies that team with them do look for good stories—well-told with interesting characters. But they also look for other things—some of which simply don’t matter to publishers. Which is why it’s possible to have a great book with little film appeal. Julie continues, “It's important to understand their mindset because the studios are your market, and you need to know their market.”

So, aside from good stories with compelling characters—what are the qualities that persuade rational corporations to put anywhere from $1 million to $400 million into a film that will rise or fall on the crest—or trough—of public opinion?

“Studios don’t want something they cannot sell. Even outside the studio system, those who invest in the film want and deserve our best efforts to ensure a profitable return.”

(Photo: Julie Richardson, Producer)

Appealing To Hollywood

It’s a brave new world for Hollywood—and a scary one. Films must now compete with big-screen TVs, cable networks, video games, free Internet videos, and a thousand other forms of entertainment that, until recently, didn’t exist. Experience has taught the studios what’s needed to meet that challenge, and they look for a number of very specific things—the most important of which are…

A CONCEPT that can be communicated in a ten-second summary called a logline. Agents and studio execs are incredibly busy and need to convey ideas to other busy people—quickly. If this cannot be done, it suggests that the story itself is not sharply focused, and that conveying the concept to its potential audience in a thirty-second trailer is going to be a problem.

While it’s true that a small minority of stories—some of them quite wonderful—cannot be boiled down to a snappy logline, these tales are both rare and incredibly difficult to sell. The reason is simple: without a logline, someone must actually read the story to gauge its potential—and almost no one has the time to do that.

An agent or producer can read seven hundred to a thousand loglines in the time it takes to read a single script. It’s more efficient to do that than to attempt to read everything. When they come across a jewel of a logline: “A fugitive doctor wrongly convicted of killing his wife struggles to prove his innocence while pursued by a relentless U.S. Marshal”, that script will be read. (A good logline can also persuade an agent or editor to read a book manuscript.)

A RELATABLE HERO whom a large segment of the movie-going public can relate to, root for, sympathize or empathize with. Audiences must care about your hero, or Hollywood doesn’t care about your story. If concept is king, character is heart—and a poor hero with heart will draw more viewers than a king without.

STRONG VISUAL POTENTIAL. Film is less flexible than print. A novel can delve inside characters’ heads and stay there for three hundred pages. Film is a visual medium, and interesting things must pass before the camera. Unless carefully adapted, introspective books make lousy movies. (When brilliantly adapted, they win Academy Awards.)

A THREE-ACT STRUCTURE. The vast majority of commercially successful films are “classically structured” into three acts. Even those with additional acts (like Star Wars) have only three major acts; the others fall within that framework.

A TWO-HOUR LIMIT, of sorts. If a story cannot be told in two hours or less (one hundred twenty script pages), it may be too costly to shoot. Film is an extraordinarily expensive medium; and when you’re footing a bill that could run upwards of $1 million per minute of screen time, you don’t want to hear that some rookie screenwriter thinks his story should run long. Seasoned veterans with proven track records warrant occasional exceptions; newcomers do not.

A REASONABLE BUDGET. In the book world, the publisher’s cost-per-page remains the same—whether your characters are playing checkers or blowing up a planet. This is not true of film where shooting two characters playing checkers might cost $200,000, and filming a major action sequence could run $10 million. If the story seems prohibitively expensive to film, it will not become a movie unless someone very powerful pushes the project very hard.

LOW FAT. Because of time and budgetary constraints, there’s little room for anything not absolutely essential to the story. Novelists can burn ten pages describing a room. A screenwriter might do this in a sentence—and going on for more than a paragraph will mark him or her as an amateur. As the old Hollywood adage states: “If you show a shotgun over the mantle in the first act, you’d better use it in the third.”

SEQUEL POTENTIAL. If a film based on your book can be sequeled and prequeled, that’s a big point in your favor. If the first movie hits, it’s a safer bet to release a sequel to your film than it is to risk vast sums on something new and untried. Sequel/prequel potential isn’t mandatory—but the more expensive the film, the more it helps. (At this moment, there are eighty-six movie sequels in development.)

“FOUR QUADRANT” APPEAL. Studios divide the movie-going public into four large segments, or quadrants: young male, older male, young female, older female. The greater the number of quadrants your project appeals to—the better. Four-quadrant appeal is the primary reason for the huge success of animated films—and of Avatar and Titanic, the two biggest grossing films of all time.

Four-quadrant appeal is not a strict necessity (the more people you pull from one quadrant, the fewer you need to pull from others)—but it’s nice to have. And if, like James Cameron, you can draw viewers from eight to eighty—you’ll be king (or queen) of the world.

MERCHANDISING POTENTIAL. Film studios make more money from film-related merchandising than they do from the films themselves. A lot more. Films with low or no merchandising potential continue to be made, but the tidal wave is moving the other way—favoring projects with strong merchandising appeal. Generally speaking, big-budget action and animation films are merchandising bonanzas while dramas, thrillers, and comedies have considerably less merchandising appeal.

Obviously, this hasn’t kept studios from making dramas, thrillers, and comedies—which are less expensive to film and therefore, don’t require the kind of Herculean merchandising blitz needed to keep a marketing juggernaut like the Batman franchise raking in the billions.

“Every Hollywood player asks one question after reading a script: ‘Is this a movie?’”

(Photo: Christopher Lockhart, Story Editor)

Making Your Story Film-Friendly

Most books are not movies. Some never will be. Most, however, could be movies if carefully adapted. There are several avenues to pursue here.

If the work is still in manuscript form, you can alter the story to make it more cinematic by adding or playing up the elements Hollywood is looking for. (Booklist’s review of article author John Marlow’s first novel read: “Reads like a big-budget summer blockbuster.”)

If you’d prefer to keep your manuscript the way it is or if your book has already been published, you can adapt the story by writing or commissioning a screenplay based on the book. In fact, you might want to consider this option even if your story is already film-friendly.

A book is meant to be read and enjoyed for what it is. A screenplay aims to roll a movie in the reader’s head so vividly that he or she says: “I want to make this movie, I want to see it on the screen, and I will pay money to make that happen.”

Christopher Lockhart is Story Editor at William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, one of the few Hollywood super-agencies. He reads and consults on scripts for top-end clients including Mel Gibson, Denzel Washington, Steve Martin, and others. In his considerable experience, every Hollywood player asks one question after reading a script: “Is this a movie?” If the answer is yes, you’ve got a shot at selling that story.

“If you’ve actually got the adapted screenplay and it’s a good screenplay, I think you have a better chance of getting it made. Because someone can look at it and say, ‘Wow, this is great.’”

(Photo: Lesli Linka Glatter, Director)

Lesli couldn’t agree more: “I think I know immediately. If I read something and I see the movie—I know I’m the right person to direct it. If I don’t see the movie, it’s probably better that someone else does it. Because the project deserves someone who’s that passionate about it.”

When courting Hollywood, it’s essential that your story be as much like a movie as possible—and the best way to do that is to present it as a screenplay. “If you’ve actually got the adapted screenplay and it’s a good screenplay,” Lesli says, “I think you have a better chance of getting it made. Because someone can look at it and say, ‘Wow, this is great.’ And that’s a big step closer to getting the movie made.”

Books raise questions screenplays don’t: Will this work on-screen? How do we squeeze four hundred pages into two hours? Half the book takes place inside the hero’s head—how do we fix that? This would cost $300 million to shoot—can we make it less expensive? Can we tell this story in three acts, streamline the plot, strengthen character arcs? If we buy the rights, who do we hire for the adaptation? How much is that going to cost? And, at the end of all that—will this be a movie?

By going in with a screenplay instead of a book, you avoid such complications and potential objections, allowing the prospective buyer to focus on that one, all-important question: Is this a movie? It comes as no surprise when Gale says, “There are more buyers for finished screenplays than for pitches.”

Lesli concurs: “Whether you’re raising money independently or going through the studios, you don’t have anything without the screenplay.” Another thing to consider is…

Money Money Money

The typical advance for a first novel is in the neighborhood of $10,000 to $20,000. The typical selling price of a spec screenplay by a first-time writer hovers between $300,000 and $600,000 with some first scripts topping the $1 million mark. (This is not true of adaptation rights alone when there is no screenplay.)

Novels run three to five hundred pages of densely-written text. Screenplays run one hundred to one hundred twenty pages of fairly light text. Do the math: on the low-end, a book (at five hundred pages and $10,000) pays $20 a page while a screenplay (one hundred twenty pages and $300,000) pays $2500 per page.

Before deciding to give up books and write screenplays, though, be aware that screenplay earnings are capped; regardless of how successful the film or television series may be, you will be paid the purchase price, bonuses, residuals, and so on—and that’s all. After that, the well runs dry—for you. The studio makes money forever.

The book world imposes no such ceiling: every copy sold puts more money in your pocket. If the book does insanely well, you make an insane amount of money. This is why there are no pure screenwriters on Forbes’ list of the world’s highest-earning writers. But keep in mind: there are no authors without film involvement either. That’s because…

The Global Market is Digital

A recent Associated Press-Ipsos poll found that only one in four American adults claimed to have read a book during the previous year. Those who did read reported going through an average of nine books—in an entire year. The AP’s article on the study referred to book sales as “flat in recent years” and “expected to stay that way indefinitely.”

As it turns out, this may be optimistic: a report released in April 2010 by the Association of American Publishers shows an overall decline in actual book sales compared with the previous year. Even a sharp increase in e-book sales could not reverse the downward trend.

Reasons cited by the poll include competition from other media and a mature publishing industry with “limited opportunities for expansion.” One respondent summed things up succinctly: “If I’m going to get a story, I’ll get a movie.”

“The plain fact of the matter is that people who won’t—or can’t—read books still watch movies.”

Our personal feelings are irrelevant. The plain fact of the matter is that people who won’t—or can’t—read books still watch movies. Bad films are seen by more people than most good books. And pollsters would be hard-pressed to find any first world resident—adult or juvenile—who’s viewed a paltry nine movies over the course of any recent year.

Industry expansion? The first large-scale 3D film—Avatar—is closing in on $3 billion at the box office, annihilating the previous record set by Titanic over ten years ago. If the typical ratio holds, the DVD release will bring that total to between $12 and $16 billion, exclusive of merchandising and other rights. For a single film. (Two sequels are planned.)

Not coincidentally, 3D televisions are scheduled to roll out this year, and a process has been developed to upconvert films originally shot in 2D to 3D. Equipment created to shoot Avatar may well revolutionize other aspects of the film world as well.

While the persistent rumors of print’s death remain highly exaggerated, it is undeniable that movies are evolving in a way that print is not. And whether we like it or not, the writing (so to speak) is on the wall (or screen): in an increasingly digital culture, entertainment becomes, well, increasingly digitized. There is, in the end, only so much we can do with printed, even digitized, words.

But while books still live, movies—and screenplays—can be used to amplify their impact and their authors’ bank accounts through…

Synergy

Having both a book and a screenplay opens up new possibilities. Mere interest in one is almost certain to increase interest in the other. The actual sale of either will make purchase of the other more likely. And in the best of all possible worlds, a savvy agent can play studio interest against publisher interest and elevate the price on book and screenplay to ridiculous heights.

If the book is published and succeeds, the screenplay is far more likely to be purchased (if it hasn’t been already) and far more likely to be produced (even if it’s already been purchased and has stalled at the studio).

If the book didn’t sell, but the screenplay does, publishers will suddenly become interested in the book. (The reverse is also true: if the script doesn’t sell and the book sells high or becomes popular, the screenplay may get a second life.)

And of course, a successful movie will resurrect sluggish book sales and push brisk sales higher. Because of the cap on screen-side earnings, a hit film can cause your book to make you more money than the screenplay ever will.

But you need the screenplay to make that happen.

“In adapting novels, the problem is often how to take interior drama and make it explicit and visually exciting.”

(Photo: Teena Booth, Screenwriter)

Adapting Your Book or Story

As mentioned earlier, film makes unique demands of the source material. Gale says, “Adaptations pose the challenge of determining which material is relevant, and it’s especially difficult—though often necessary—to lose compelling scenes and characters from the underlying source material.”

Teena Booth agrees. “In adapting novels, the problem is often how to take interior drama and make it explicit and visually exciting.”

“I think it’s very hard to adapt,” adds Lesli. “To create the kind of experience that people can see taking place on the screen. You have to strike a delicate balance between being true to the original material and story concept and translating it into this other, very visual medium.”

True stories present their own issues. “I usually adapt true stories,” says Teena. “And my biggest challenge is to come up with a dramatic arc for the main characters or a suspenseful arrangement of events—elements frequently missing from a book or article.” These same elements are often missing—or less-than-fully realized—in unpublished (and some published) fiction manuscripts as well.

“Obviously, true stories don’t follow traditional plot lines, and that offers up both opportunities and obstacles along the way,” Gale adds. “It’s important to be able to see the forest and not just the trees.” Most book authors facing their first adaptation get lost in the trees.

So, who will see the forest? Once you’ve decided to adapt your book or other story, you have three basic choices: write the screenplay yourself, get some help, or hire someone to write it for you…

Write It Yourself

This costs you nothing but time. But don’t let that one hundred twenty pages fool you—a screenplay can be every bit as difficult to write as a novel. And it can take even longer to write. The peculiar challenge of the screenwriter’s art is to say more with less, using fewer words to convey greater meaning. For those unaccustomed to the format, this takes a surprising amount of time.

“The peculiar challenge of the screenwriter’s art is to say more with less, using fewer words to convey greater meaning.”

“As with any career, it’s critically important to practice and hone your craft,” Gale advises. “Join a writer’s group or two; and write, write, write. Find your original voice, and look for stories and characters that speak to your background and what is unique in your worldview.” Is screenwriting success more difficult for women than for men? Gale’s experience tells her no: “I don’t believe there are, or should be, different rules for male and female writers.”

In other words, it’s equally difficult for everyone—and the most difficult transition of all is going from novelist to screenwriter. Novelists tend to write long (by Hollywood standards); and overly descriptive writing is the surest mark of an amateur scriptwriter. In this sense, much of the novelist’s experience works against him or her.

How long does it take to become a good screenwriter? In most cases, the answer is years. You can speed that up if you…

Consult with an Experienced Screenwriter

Or, better yet, screenwriter/novelist or adaptation specialist. They can review your story with a practiced eye toward screen potential and suggest specific points/changes to consider during the adaptation. The trick is to find the right person (more on this below), and then work with them on a detailed outline for the screenplay—before writing it.

With professional input and some story flexibility on your part, this should provide you with a solid three-act structure, proper pacing, a relatable hero, and good character arcs. Of course, it’s still up to you to make all of that work. Check in with your consultant every thirty pages or so for feedback on your progress.

Approaching the task in this way can accelerate your learning curve tremendously and is a good idea even if you plan on writing an original (non-adapted) screenplay. Still, if it takes you a long time to become a good screenwriter, those consulting fees can add up—quite possibly to the point where it would have been cheaper to…

Hire a Screenwriter or Adaptation Specialist

Hiring someone who knows their way around a screenplay is the fastest way to ensure quality results. “Writing is the most difficult aspect of filmmaking,” says Gale. “Staring at a blank page and having to fill it with meaningful stories and well-rounded characters is the most daunting challenge in the business. And while there are exceptions, I would generally recommend approaching professional screenwriters or producers to undertake adaptations—because it’s a rare author who has sufficient objectivity to make the best choices when adapting their own material.”

“While there are exceptions, I would generally recommend approaching professional screenwriters or producers to undertake adaptations—because it’s a rare author who has sufficient objectivity to make the best choices when adapting their own material.”

Lesli seconds that. “When the work you’re adapting is your own, you’re obviously intimately connected to it—making it that much harder to step back and be objective about the changes that have to be made. That’s a huge challenge.”

Teena Booth agrees, noting that while some books might appeal to some TV markets without adaptation, others “don’t necessarily scream commercial appeal and may be impossible to sell without the buyer seeing a script.”

But who to hire? Most screenwriters with produced credits belong to the WGA (Writers Guild of America)—an organization whose rules prevent members from accepting less than a $50,000 to $90,000 minimum for feature-length work. Those at the top of the game routinely charge $1 million or more. If you can afford that, and your writer has adaptation experience, your search is over. If not, read on.

You need to find someone who’s good—but most likely unproduced. The dilemma then becomes: How can a book author with little or no Hollywood experience (you) be reasonably sure that a probably unproduced screenwriter knows his or her stuff? The answer is simpler than it might seem: rely on the opinions of those who do have Hollywood experience.

One way to do this is to look for someone who’s been optioned by a real producer or company or someone who’s been “in development” with a real company or filmmaker. If film industry professionals have shown strong interest in your writer’s work, that means a lot—and sets him or her apart from the cast of thousands of would-be screenwriter/consultants who have no real industry experience.

You can also look for someone who’s placed very highly in a prestigious screenwriting competition. And you should know that there are many script contests of questionable integrity—designed more to fatten the wallets of their creators than anything else. Placing highly, even winning one of these, may mean little.

The Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting program, on the other hand, stands head and shoulders above all other screenplay competitions. It’s run by the same organization that hands out the Academy Awards. Gale sits on the committee that judges the finalists. Thousands of writers submit their scripts each year, but only ten scripts are declared finalists. Those who’ve reached this level have gone on to write films like Air Force One, Arlington Road, Armored, Erin Brockovich, Pocahontas, Transformers 2, 28 Days, and the Castle TV series. (The Chesterfield, another prestigious fellowship, is no longer active.)

Given a choice, you also want someone who knows what it’s like to write and adapt a book because they’ll have a better understanding of where you’re coming from, and what it takes to get your story from three hundred-plus pages to one hundred twenty. A published novelist or nonfiction book author who is also an accomplished screenwriter is a good find. An adaptation specialist is ideal.

“You need a writer who sees the story as you do and will keep its ‘heart’ alive and beating strongly in the new medium.”

Lastly, you need a writer who sees the story as you do and will keep its “heart” alive and beating strongly in the new medium. Be open to changes—but also know when to say enough is enough, that this is no longer the story you want to tell. Again, work with the screenwriter or adaptation specialist to create a detailed outline before the writing begins. Any significant departure from the outline should be approved by you in advance.

Check with your screenwriter or specialist every thirty pages or so to be sure things are going as planned and consult again at the end before the “polish”. It can be a powerful learning experience to see screenwriting principles applied to your own work—and one that cannot quite be duplicated in any other way.

Keep in mind that, like everyone else, screenwriters have bills to pay. Asking a writer to work for nothing up front, and a percentage of the sale price only if and when the script actually sells, is a classic amateur move. (Would you write someone else’s book based on such an offer?)

As Rocky Balboa once said, “It’s simple mathematics.” If the screenwriter writes his own script and sells it, he gets 100 percent of the money—so why set his fabulous ideas aside to work on yours? Great ideas are more common than you might think. Doing those ideas justice for the duration of a screenplay or novel is rare. That’s what good writers are paid to do.

What then? As with publication, the road from script to screen is seldom easy—but those who do get their projects consistently made in this town share a single defining attribute:

Passion

“Once you have the screenplay, you need a bit of luck—but also persistence,” says Teena. “Knock on every door you can find, and don’t stop trying.”

Lesli also casts her vote for “tenacity. Don’t accept no. Just keep at it. You can have hundreds of nos, but all it takes is one person who says yes.”

Gale agrees. “Work hard, be passionate about your projects, and persevere when the going gets tough. Jim [Cameron] and I had twelve passes on The Terminator. We were down to our very last pitch—and sold it on the thirteenth try.”

“When I started twenty years ago, I didn’t know anybody,” Lesli relates. “I did a film that got people’s attention—a little film on no money—and I’ve been doing this ever since. So I have to believe that when push comes to shove, it is in the end about the quality of the work.”

When a producer, director, or star becomes truly passionate about a screenplay—falls in love with it—she (or he) will go to extraordinary lengths. After producing the Tom Cruise/Jaime Foxx thriller Collateral (written by Stuart Beattie), Julie Richardson came across a romantic comedy script she couldn’t live without. The only problem was—no one could find the writer.

“Unable to locate the writer on her own, she hired a private detective to track him down—and then optioned the script, which is now in development.”

“I wanted this script,” Julie recalls. “And by God, I was going to get it.” Unable to locate the writer on her own, she hired a private detective to track him down—and then optioned the script, which is now in development. (That writer, John Marlow, is one of the authors of this article.)

It’s often said that Hollywood is more about whom you know than what; and many writers spend vast amounts of time trying to connect with people in the industry. But if you can craft a screenplay that gets readers passionate about characters and story—Hollywood will want to know you.

And that, ultimately, is what you want.

***

The content of this article is copyright © by John Robert Marlow, all rights reserved.

Jacqueline Radley is a screenwriter, script consultant, and former story editor for a major Hollywood producer. She wrote and produced television documentaries for six years.