o you love ferreting out facts to share with others? Researching until you find something new? Then children’s nonfiction may be the niche for you.

True, school and library budgets aren’t what they once were, but neither is children’s nonfiction. Gone is the ho-hum dry material I read in school. Editors today want high impact, exciting nonfiction. You just need to learn how to give it to them, and the answer may surprise you.

The first thing that many nonfiction editors mention is story.

“Whether you are writing fiction or nonfiction, dialogue pulls readers in.”

Tell Me a Story

Narrative nonfiction tells a story that is 100 percent factual. This means, of course, that you aren’t making things up. You are, instead, choosing a dramatic topic with a natural story arc and finding the right facts to support it.

This is what Carla Killough McClafferty did in The Many Faces of George Washington. It isn’t a biography. That’s been done. Instead, she tells a story about how a team of experts struggled to discover what George Washington really looked like. The first step in adding tension to the story? She reveals that in spite of proximity to his grave, the experts couldn’t examine Washington’s remains. With possible answers so close, they had to look elsewhere. Instant tension!

Whether you are writing fiction or nonfiction, dialogue pulls readers in. Some early nonfiction writers invented dialogue. Not so for the narrative nonfiction of today. Each and every word contained within a writer’s quotation marks must be documented. To do this, authors examine letters, journals, and speeches. What does an author like McClafferty do when she can’t find the dialogue she needs to make her story stronger?

She interviews an expert. McClafferty spoke with James Rees, the president of George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate and gardens about the misconception that led researchers to seek out Washington’s true appearance.

...when participants were asked what they thought of Washington when they saw the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait, many responded by using words like “stiff,” “old,” “grumpy,” and even “boring.”

Their comments surprised Rees, who said, “Boring is not a word anyone in the eighteenth century would have used to describe George Washington. He was the most robust, athletic, outdoorsy, and adventurous of all the founding fathers. He was the man of action of the eighteenth century. The real Washington made heads turn.”

Rees’s dialogue works two-fold. It increases the tension—Washington was not how many of us perceive him—but it also gives us insight into both Washington and Rees, two of McClafferty’s characters.

Just as today’s nonfiction tells a story, the people within it serve as characters. In McClafferty’s book, the characters range from historians to scientists and even Washington himself. They are revealed through their words, the conflicts they have with each other, and their actions.

McClafferty doesn’t just tell us what the characters did. She uses a scene to show us what happened when Jean-Antoine Houdon, the artist who created Washington’s life-sized sculpture, witnessed Washington interacting with a horse dealer:

One morning Houdon followed Washington as he met a man who came to Mount Vernon, hoping to sell some horses. Washington looked over the horses and asked the man how much he wanted for them. When he heard the exorbitant price of the horses, a look of indignation crossed his face. Washington thought the man was asking far too much for them. He suggested the horse trader take his horses and leave Mount Vernon. That look was the one Houdon had been waiting for—George Washington was proud, firm, and convinced he was right.

How much more intriguing is that than a straight fact dump, which might read something like this: “Houdon watched Washington negotiate for some horses. The price was too high. Washington told the man to leave. Houdon saw the look on Washington’s face. This was the look for the statue.” I’m sorry, did I put you to sleep? Scenes work by pulling the reader into the story.

But not all of today’s nonfiction is built around a fascinating story. Sometimes, it is all about getting information across to the reader.

“...design elements work to convince young readers that this is a book that they can get into.”

Informational Nonfiction and How It Works

Informational nonfiction gives the facts without any narration. There is no attempt at story or strong scenes. This doesn’t mean that informational nonfiction doesn’t have to hook its readers. It just does it in a different way.

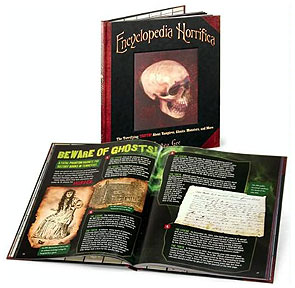

A large part of the hook comes through book design. These designs often emphasize fun with color images, sidebars, and other visual elements used to break up the text. Some books, especially those about magic or monsters, may be designed to look old and well worn. Others have 3-D images. All of these design elements work to convince young readers that this is a book that they can get into.

Topic also plays a large role in informational nonfiction. Some topics have instant kid appeal such as How to Convince Your Parents You Can...Care for a Kitten by Stephanie Bearce or the humorous How to Build Your Own Country by Valerie Wyatt and Fred Rix. Even in informational writing, humor can help hook your reader. Other topics include current hot button subjects and may be published in series, such as Gareth Stevens Publishing’s Energy for Today series with titles like Solar Power,

Wind Power, and Ethanol and Other New Fuels. Still others are almanac style books, often created with boy readers in mind. Examples include Encyclopedia Horrifica by Joshua Gee and The World Almanac for Kids.

Many nonfiction topics can be written as either narrative or informational titles. Before deciding which you will write, take a look at the full range of children’s nonfiction.

“The audience for children’s nonfiction ranges from toddlers to teens, so finding the right fit and format for your idea are vital.”

From Board Books to Educational Series

Part of what makes writing children’s nonfiction challenging is picking the correct form for your manuscript. The audience for children’s nonfiction ranges from toddlers to teens, so finding the right fit and format for your idea are vital.

Board Books:

Named for their construction, board books are made from heavy card stock to survive enthusiastic handling from toddlers and preschoolers. Nonfiction board books cover basic concepts and simple stories and are frequently written by author/illustrators or may be developed in-house. They can be a tough sell for authors who don’t also illustrate.

Books to study:

Little Black Book by Renee Khatami

Brush, Brush, Brush by Alicia Padron

Summer by Roger Priddy

Funny Tails by Liesbet Slegers

Picture Books:

The audience for nonfiction picture books ranges from preschoolers to older elementary school students, but no one book will appeal to this entire range. Many nonfiction picture books are used in schools, so you need to identify your audience and make certain that your topic corresponds with educational standards for that age level. Because picture books are usually thirty-two pages long, they are not comprehensive studies, but generally examine one element of a topic.

Books to study:

The Secret World of Walter Anderson by Hester Bass

Mammoth Bones and Broken Stones by David Harrison

Dinosaur Food by Rupert Matthews

The Grand Mosque of Paris by Karen Grey Ruelle

Beginning Readers:

Composed of shorter sentences and often using controlled vocabularies, beginning readers pull new readers into the experience of reading without adult help. Each publisher uses a slightly different format, so check their guidelines before submitting. Again, check educational standards to make sure your topic is in line with what students are studying, and you will have a better chance of selling your work.

Books to study:

Betsy Ross: The Story of Our Flag by Pamela Chanko

All the Colors of the Rainbow by Allan Fowler

Life in a Pond by Allan Fowler

Clouds by Anne F. Rockwell

Ants by Melissa Stewart

Middle Grade and Young Adult:

The range here is as vast as is picture book nonfiction. Titles for tweens and teens include those that correspond to school topics, self-help, and craft topics as well as things they might want to research on their own, including controversial issues like cloning or global warming.

Books to study:

An Unspeakable Crime: The Prosecution and Persecution of Leo Frank by Elaine Marie Alphin

The Hive Detectives: Chronicle of a Honey Bee Catastrophe by Loree Griffin Burns

The Dark Game: True Spy Stories by Paul Janeczko

Kakapo Rescue: Saving the World's Strangest Parrot by Sy Montgomery

Educational Series:

Many nonfiction titles are published within established series by educational publishers such as Lerner and Capstone. To write for one of these series, check the writers’ guidelines. Some publishers accept series suggestions, while others want to receive an author’s resume and samples before assigning a topic. Often writing for an established series means writing in a work-for-hire capacity.

Magazines:

Children’s magazines range from Babybug for the youngest readers to Seventeen for older readers. Some publications, such as Jakes, have a fairly narrow focus while others, including Highlights for Children, are much broader. Information that wouldn’t fit into a book can easily make a magazine piece while also adding to your credentials. Many magazines also use more nonfiction than fiction, although what they actually receive from writers is heavier on the fiction end.

“Publishers absolutely don’t want books on saturated topics...”

Sometimes the Answer Is No

Even if you have carefully studied potential markets, rejections happen. To improve your chances of making a sale, avoid these common problems.

Been There, Done That:

Publishers absolutely don’t want books on saturated topics, so a biography on George Washington would be a tough sell. McClafferty made her sale by combining forensic science and art to breathe new life into a familiar topic.

Obscurity:

Publishers won’t publish what is already out there, but they don’t want anything too isolated either. A book on a little known pioneer in aviation may not sell even if he is a local hero. Link him to someone like Charles Lindbergh, and you may change this. Even if your topic is fascinating, the publisher has to find enough readers to make it financially worthwhile.

No Curriculum Connections:

Because of the need for a broad audience, books with no curriculum connection are often rejected. This doesn’t mean that you should give up on your dream of writing about the history of jawbreakers, but it does mean you need to find the right age level and how you can tie it into the curriculum. Show your editor the marketing edge.

Lack of Sales for Someone Else:

Even if your topic has broad enough appeal, a built-in audience and a curriculum tie in, you still might find yourself facing a rejection. Why? Because your work will also be rejected if this topic simply is not selling. While you shouldn’t write to trends, have some idea what people are interested in right now. It will, after all, give you a much better chance to sell your story.

Between the research and market studies required, there’s no doubt about it. Writing children’s nonfiction is a lot of work. But the fact remains—young readers of all ages are hungry for information.

Why shouldn’t you be the writer to fill that niche?

***

Sue Bradford Edwards is a nonfiction author with over 600 sales to her credit including 24 nonfiction books for young readers. Sue has also published numerous crafts, activities and how to pieces of various kinds. Her most recent books for children and teens are The Murders of Tupac and Biggie (Abdo, 2020), The Assassination of John F. Kennedy (Abdo, 2020), The Evolution of Mammals (Abdo, 2019), The Evolution of Reptiles (Abdo, 2019), Labradoodle: Labrador Retrievers Meet Poodles! (Capstone, 2019), Puggle: Pugs Meet Beagles (Capstone, 2019), Stem Cells (North Star Editions, 2019), The Dark Web (Abdo, 2019), and Earning, Saving and Investing (Abdo, 2019). In addition, her children’s nonfiction has appeared at Education.com, in Gryphon House anthologies, in Harcourt and Houghton Mifflin testing packages and also in READ and Young Equestrian Magazine. Her nonfiction for adults has been published in Writer’s Market, Children’s Writer newsletter, WOW! Women on Writing, Writer’s Digest, The Children’s Writer’s and Illustrator’s Market, The Writer’s Guide, and Magazine Market’s for Children’s Writers. Sue is also a dedicated blogger, writing for the Muffin as well as her own personal blog, One Writer’s Journey. Sue is an instructor for WOW! Women On Writing and teaches a workshop on researching and writing nonfiction for children and young adults. Visit the Classroom for a current class schedule.

-----

Enjoyed this article? Check out these related articles on WOW!:

Write Nonfiction for Kids? Break Out with a High-Concept Idea: Interview with Carla Killough McClafferty

Finding the Micro-Niche in Science Writing for Children

Writing for the Educational Market

How to Lower the Reading Level of Your Story

Recovering from Injury: Bouncing Back from a Rejection Letter

How to Write a Picture Book