all me crazy, but I swear a dancing hippo is reenergizing my writing.

And if I am crazy, I’m not any crazier than Isabel Allende, Steven Pressfield, or Charles Dickens—at least not where the dancing hippo is concerned. And I have evidence from neuroscience to back me up.

What do I have in common with Allende, Dickens, Pressfield, and with a whole host of other writers, including Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Eudora Welty, Mark Twain, Virginia Woolf, Aaron Sorkin, Victor Hugo, and Lewis Carroll? We all know the power of a writing ritual.

Isabel Allende lights “candles for the spirits and the muses,” surrounds herself with fresh flowers and incense, and meditates to open herself to her writing on a regular basis.

Charles Dickens felt the need to move the ornaments on his desk into a specific order before starting to write.

Steven Pressfield describes his elaborate prewriting routine in The War of Art, a ritual that includes reciting Homer, wearing lucky boots with lucky laces and a lucky sweatshirt, a lucky charm from a French gypsy, an acorn from the battlefield of Thermopylae, a cuff link, and a cannon placed on top of a thesaurus, “so it can fire inspiration into me.”

Novelist John Edgar Wideman observed, “The variations are infinite, but each writer knows his or her version of the prepatory ritual must be exactly duplicated if writing is to begin, prosper.”

“Writers need rituals to distract us from thinking too much about how we do what we do.”

[Photo: Virginia Woolf walked before writing.]

Sensibly Irrational

Robert Olen Butler observes that just like athletes, writers need rituals to distract us from thinking too much about how we do what we do. Thinking too much invariably causes a slump.

In From Where You Dream, Butler points out, “If it’s technique, you think about it. If it’s your socks, it’s not rational. What superstitions do for the athlete is to irrationalize. And that’s what you have to do as a writer; you have to irrationalize yourself somehow.”

My writer’s ritual in irrationality happens to include a dancing hippo, which I think is nowhere near as strange as Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette who picked fleas from one of her twelve cats before starting to write, or Honoré de Balzac who needed to don a dressing gown that looked like a monk’s robe before he began.

Positioning a toy cannon so it can fire inspiration into you, needing to sharpen twenty pencils by hand, writing in the nude or in your bathrobe, and using different colored paper and pens for different kinds of writing are all perfectly irrational.

And at the same time, these rituals make perfect neurological sense.

Neurology of Ritual

The power of writing rituals lies within Hebb’s Law, which states, “Neurons that wire together, fire together.”

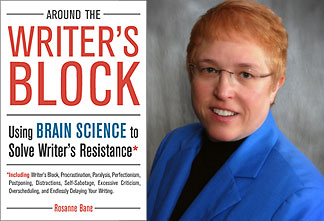

In my book, Around the Writer’s Block: Using Brain Science to Solve Writer’s Resistance, I explain, “When a group of neurons that process one movement, sensation, or behavior are frequently activated at the same time that another group of neurons responsible for another movement, sensation, or behavior are activated, those two groups of neurons will begin to make connections and fire simultaneously.”

You can combine two completely unrelated experiences into one ritual through repetition. There is nothing about a dancing hippo or lemon drops, for example, that would compel a person to write.

But I highlight in Around the Writer’s Block: “If the neurons for smelling lemons [or in my case seeing and hearing an animated hippo dance to “I Like to Move It”] are activated at the same time that the neurons you use when you’re writing are activated, those two groups of neurons start to form a connection; they ‘wire together.’ Repetition reinforces this connection, so that eventually firing one set of neurons causes the other set to fire as well . . . Eventually just smelling lemons [or playing the “I Like to Move It” clip] will trigger the neurons used for writing and you’ll ‘feel’ like writing.”

Instead of waiting passively for inspiration to strike, you can create the neurological patterns for “inspiration” inside your brain with your own writing ritual.

“The more senses a ritual engages in unusual ways, the more powerful it is.”

[Photo: Truman Capote wrote lying down, with a glass of sherry in one hand and a pencil in another.]

Practice, Practice, Practice

Repetition is the key to developing a ritual. When a group of neurons fire in a particular sequence, that neural pathway gets a thin layer of myelin. Myelin is the fatty, white tissue of the brain that insulates the connections between neurons and makes a neural pathway more efficient and fast.

Every time a neural pathway is activated, it gets another layer of myelin. What we call a habit or a ritual is simply a well-myelinated pathway.

Haruki Murakami, author of Norwegian Wood and several other novels, emphasizes the importance of repetition. “I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

The Weirder, the Better

You need more than repetition to create a strong writing ritual. Andrew Newberg, Eugene D’Aquili, and Vince Rause point out in Why God Won’t Go Away: “Every ritual turns a meaningful idea into a visceral experience.”

You need to feel a writing ritual, not only think about it. But it’s still vital to think about what you’re doing and why, especially when you first build your writing ritual. The brain changes only when we’re paying attention, and the brain pays attention to what’s changed, unusual or weird.

Newberg, D’Aquili, and Rause’s observations may explain the elaborate movements involved in Dickens and Pressfield’s rituals. “Rituals often incorporate specific ‘marked actions’ . . . action that by its form or meaning draws attention to itself as being different from ordinary practical movements.”

The more senses a ritual engages in unusual ways, the more powerful it is. German playwright Friedrich Schiller said that the smell of the rotten apples he always had in a desk drawer kept his imagination alert, and he claimed he couldn’t write without the smell present.

May Sarton listened to eighteenth century music. Steven Pressfield recites Homer. You can pair writing with bells; white noise; or the background sounds of a coffee shop, bookstore, or train. Peter Brett, Julie Klam, Robert Olen Butler, and other writers use the sounds, vibration, and feel of trains as part of their writing routines.

Perhaps the most intimate way to feel a ritual is through what we wear. Just think of all the writers who, like Pressfield, have lucky writing shirts, shoes, hats, socks, etc. John Cheever is noted for doing most of his writing in his underwear. Victor Hugo and Ernest Hemingway wore their birthday suits.

What Rituals Can Do for You

“It’s vital to establish some rituals—automatic but decisive patterns or behavior,” writes Twyla Tharp in The Creative Habit, “at the beginning of the creative process, when you are most at peril of turning back, chickening out, giving up, or going the wrong way.”

Tharp credits rituals for eliminating doubt, putting us in motion, and giving us the confidence to keep going.

Susan K. Perry, Ph.D.—social psychologist, creativity blogger, and author of Writing in Flow—says, “Doing the ‘easy’ thing, like grabbing your lucky writing mug will ease you painlessly into the harder thing—facing the page and waiting for the words to begin flowing.”

A ritual’s ability to ease anxiety isn’t just a way to make you feel better. Because rituals are so familiar, they soothe the limbic system, sometimes called the mammal brain or the emotional brain. An agitated limbic system will override the creative cortex’s desire and ability to write—this is the neurological reality that underlies writer’s block and other ways we resist our writing.

Rituals not only make it possible to write and make you want to write; rituals will make you need to write.

Addicted to Writing? The Neurology of Craving

Wolfram Schultz, professor of neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, trained a macaque monkey named Julio to anticipate blackberry juice when he saw colored shapes appear on a computer screen, just like Pavlov trained dogs to anticipate food when he rang a bell.

Unlike Pavlov, who could only speculate about what was happening, Schultz was able to record how Julio’s brain activity changed. At the start, Julio saw a shape on the computer screen (cue), pressed a lever (behavior), then received the blackberry juice (reward), which caused activity in his reward circuits to spike.

As Julio learned to associate the shapes with the juice, his reward circuits spiked before he received the juice. The sight of the cue—the shape on the screen—triggered the reward response pattern in Julio’s brain before he pressed the lever, even though the reward—blackberry juice—didn’t arrive until after he performed the behavior.

Even more interesting, when Schultz changed the pattern so that Julio received his reward only some of the time, Julio’s brain activity showed the anticipation and frustration patterns of craving. It was no longer just a pleasant coincidence that juice was partnered with paying attention to shapes on the computer screen; the reward was expected and necessary for the brain to maintain normal functioning.

Charles Duhigg writes in The Power of Habit, “This, scientists say, is how habits emerge, and why they are so powerful: They create neurological cravings. Most of the time, these cravings emerge so gradually that we’re not really aware they exist. But as our brains start to associate certain cues with certain rewards, a subconscious craving emerges.”

“If you’d feel a little embarrassed doing your ritual in the presence of another person, you’re on the right track.”

[Photo: Mark Twain wrote in bed.]

Design Your Writing Addiction, I Mean Ritual

Your writing ritual can incorporate any cues you choose. You can strengthen an existing ritual, revive a previous ritual you’ve fallen out of the habit of using, or create a new ritual out of just about any smell, taste, sound, sight, texture, movement, or behavior. You can do this because your brain is plastic.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to grow, heal, learn, and change over your entire lifetime. Experience, especially repeated experience that you pay attention to, changes the neural connections in your brain.

In Around the Writer’s Block, I put it this way, “In response to your life experiences, your brain has created and recreated, wired and rewired connections and neural pathways. So even though your brain is basically the same structure as other human brains, it is as individual as your fingerprints.”

Include several sensory cues in the ritual you design. Consider what you want to see, hear, smell, taste, and feel when you start writing and what unusual—even weird—movements, gestures, or behaviors you can incorporate. If you’d feel a little embarrassed doing your ritual in the presence of another person, you’re on the right track. But your ritual should be pleasant, so it will trigger your reward circuits.

The more exclusive the cues are to writing, the stronger your ritual will be and the faster you’ll create it. So if you want to drink coffee throughout the day, don’t make coffee an element of your writing ritual. A distinctive tea that you’re willing to drink only when you’re writing will serve you better.

If you’re strengthening an existing ritual or reviving an old one, your brain might use neural pathways that already exist. If you’re creating a new ritual or adding new elements to an existing ritual, your brain will create new pathways.

At first, you might feel a mild familiarity, if some cues were part of a previous ritual; but if this is a new ritual, you will not feel any particular connection between the new cues and the urge to write. The ritual is more a theory at this point, not yet a visceral experience. As you repeat your ritual over weeks, the neurons will wire together.

In the beginning, your reward circuits will respond after you experience the pleasurable parts of the ritual (the taste of a lemon drop, the rhythms and tones of a song you enjoy, the sensation of positioning things on your desk in a special way) and the satisfaction of writing itself.

Over time, your reward circuits will respond to the first cue of the ritual (the feel of the lemon drop in your hand before you taste it) before you experience the reward of the ritual and writing. You’ll start anticipating the rewards of writing.

You may never crave writing the way an addict craves a hit, but your weird writing ritual will make you want to write more than you ever did before. I never thought the rhythm and vocals of Will.I.Am and the sight of an animated hippo shaking what her mama gave her would trigger my urge to move words—and hopefully readers—either.

When it comes to writing rituals, weird works.

***

Rosanne Bane is a creativity coach and author of Around the Writer’s Block: Using Brain Science to Solve Writer’s Resistance. She is a self-proclaimed brain geek who strives to translate what neurologists and other brain scientists discover and apply that to the writing process. In more than twenty years teaching at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis, University of St. Thomas, University of Minnesota, and other adult education programs, she has given thousands of writers the tools to bust through blocks, build effective writing habits, and achieve their writing dreams and goals.

Read more from Roseanne at her blog, www.BaneOfYourResistance.com, or on her website, www.RosanneBane.com. Connect with her on Facebook at www.Facebook.com/AroundTheWritersBlock and www.Facebook.com/AWBWritersGroups.

-----

Enjoyed this article? You may also like:

The Music vs. The Muse

Retrain Your Brain